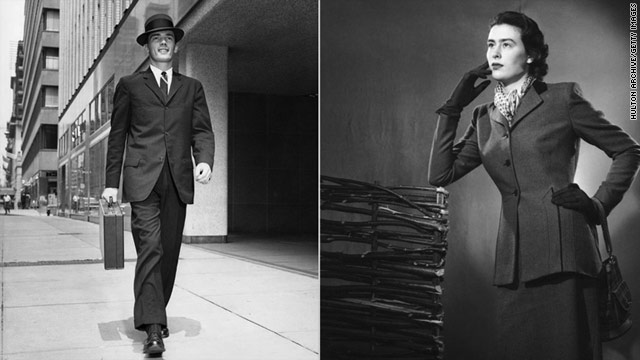

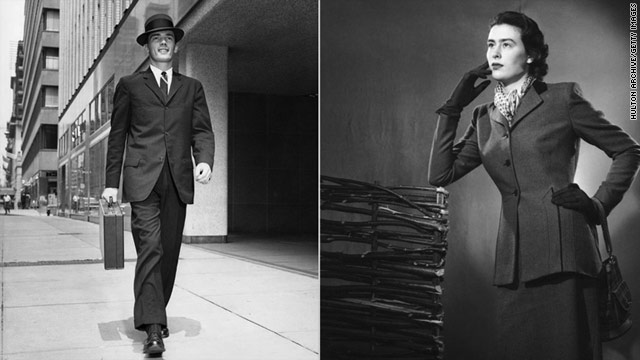

For women, knowing when to display "male" behavior at work can impact their chances of getting a promotion, study says.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS(CNN) -- Tilia Wong worked in construction management before going to business school and got used to thinking of herself as a businesswoman who knew how to keep assertive behavior under wraps.

"I'm a 24-year-old Asian girl telling a 55-year-old white guy what to do. I had to tone it down," she said of her workplace experience.

Fast forward to this year, when Wong began an MBA at Stanford University and had to reassess herself because classmates told her she was actually on the aggressive end of the spectrum.

Research shows that salary bumps and promotions can depend on how you act on the job -- but as Wong has learned, nobody seems to know where, exactly, a businesswoman should fall on the spectrum between "acting like a lady" or asserting herself "like a man."

"For the women who are a little softer, a little gentler, everyone tells them, 'You have to be firmer, more aggressive,'" she told CNN.

It's not that aggressive women need to scale it back and act like a lady -- in certain situations they need to call on those behaviors.

--Olivia O'Neill, George Mason University School of Management

"And if you come on aggressive, they tell you, 'You have to tone it down, you have to be softer.' I haven't found someone about whom they say, 'You've got it exactly right.'"

But new research suggests that the frustrating balancing act Wong describes can actually be more effective than finding a sweet spot somewhere on the spectrum and sticking to it.

"Sometimes you need to be more extreme, depending on the situation. It's not that aggressive women need to scale it back and act like a lady -- in certain situations they need to call on those behaviors," said Olivia O'Neill.

She's a professor at George Mason University's School of Management and author of a forthcoming study in the Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology that found that knowing when to display mannerisms often associated with men is more important than perfecting a one-size-fits-all persona.

"The key is to have an expanded repertoire or a tool box of traits that you can call on in professional situations," she said. "People get the mistaken impression that there's something desirable about being consistent in all contexts."

O'Neill isn't making any claims about which qualities are, or should be, innate to men or women -- she studies the cultural expectations associated with gender, and how those conflict with the demands of a corporate job.

She and her co-author, Charles O'Reilly of Stanford University's Graduate School of Business, studied 132 MBA graduates -- nearly half of whom were women -- over eight years. They assessed each graduate's relative masculinity or femininity when it came to workplace values, using stereotypical measures of masculine (assertive, aggressive, confident) and feminine (supportive, submissive, sensitive).

They found that "although masculine women are seen as more competent than feminine women, they are also seen as less socially skilled and consequently, less likeable and less likely to be promoted."

But this double bind wasn't the end of the story. O'Neill said one group of businesswomen in the study had gotten good at not trying to fulfill every expectation, all the time. Self-monitoring -- the ability to adapt behavior depending on the situation -- made all the difference for these women.

Their research found that "masculine" women who were good at switching that behavior on and off received more promotions than men, and three times as many promotions as women with the same "masculine" qualities who didn't vary their routine.

"It's not fate, a lot rests on the behaviors and the choices that you make along the way," she said. "You need to be an amateur anthropologist, go into the situation and really pay attention very carefully to what is really happening."

"When in doubt, if you mirror other people's behaviors, they tend to like you more," O'Neill said, noting that some fields have practiced this for years. "In client-facing organizations, everyone has to learn this chameleon-like behavior to fit in with the client."

According to Alice Eagly, a social psychologist at Northwestern University whose research on social roles helped identify the "masculine" and "feminine" stereotypes that O'Neill was studying, women need to view the gendered expectations in the workplace as a labyrinth -- one that they can figure out, given a little experimentation and feedback.

"Knowledge is power -- if you understand more about it, you'll do better," she said.

"The glass ceiling is no longer a good metaphor if it ever was -- it suggests that there are these absolute barriers and they're at a high level. That is actually wrong, because women have less career progress than men at all levels, including at the very beginning," she said.

By tracking business school grads over the course of their careers, O'Neill got a sense of how this process of getting ahead or falling behind starts early and never lets up. The key is knowing when to lay on the aggression, selectively, from the start, she said.

"The best way to get a raise is to have a good salary to start with -- if you go to a place straight out of your MBA and you do your negotiation, that's going to be predictive of what you have for the rest of your career," O'Neill said. "You want that negotiation to be a tough one."